ii. Cheng Beng: On love, death & tradition.

The second essay ft. smoking pyres, paper cars and clam-shells.

There’s something ironic about having to learn your own culture on Wikipedia.

Back in New Zealand, months before we left for Malaysia, I found myself Googling Cheng Beng, the festival we were timing our trip for. I had a vague idea of the event—the last time we observed it I might’ve been around eight. Mostly, I remembered sitting on the hot, dusty ground while the adults performed the rites. For my part, I followed whatever orders were given to me: kneel here, light incense here, pray here, stand here, eat this.

As a child, I was largely uninterested in these traditions, and the traditions were largely uninterested in me. I was the black-sheep cousin, an oddity born and raised in Aotearoa, so no one bothered explaining what was going on. Around me, adults chatted over my head in Hokkien and Cantonese and handed me forks in lieu of chopsticks.

But although my extended family had little faith in me, writing me off as an honorary 鬼佬 | gweilo, my Mum and Dad had always tried to instill our traditions in me. Recently, that meant spending long hours talking about their childhoods and dragging me around to temples according to the lunar calendar.

On the subject of Cheng Beng though, they were uncharacteristically vague. All I knew is that we would be visiting some graves. I imagined bringing dramatic bouquets of flowers and standing around weeping under gothic lace umbrellas dressed all in white—the traditional mourning colour. Perhaps someone would dab at their eyes with a silk handkerchief. But that couldn’t have been further from the truth.

According to Wikipedia, Cheng Beng—also anglicised as Ching Ming, Cheng Meng or Qing Ming, and translated as “All Souls’ Day”, or “The Tomb Sweeping Festival”—falls in early April each year. As I would later find out, the rituals could be observed either 10 days before, or 10 days after the date of the festival itself.

This year, Mum picked the date our family would visit my maternal grandparents: the first Saturday of April. At six in the morning, my family left our hotel and drove to my maternal aunt-in-law, or 阿妗 | Ah Kim’s house. There, three car-loads of my maternal relatives proceeded in convoy to the grave-site. When we arrived at eight in the morning, some families were already leaving, having started their ancestral venerations at dawn.

The roads leading to the graveyards were saturated with cars full of families, each competing to muscle into the narrow dirt road that led to its interior. Along the sprawling hillside, dozens of cars were already crammed end-to-end, red clay earth caked on their wheels. Just off the thin dirt track, mound after mound of round stone graves stretched into the distance. Some bore signs of recent Cheng Beng rites, while others were overgrown and covered in dirt. By the entrance, the oldest graves—some of them hundreds of years old—were beginning to crumble. Barely awake, I stared at the scene, mouth agape, as my cousin, unfazed, skillfully navigated the slippery gravel road, around potholes and up winding hills.

As we stepped out of the car, the heat of the morning and the thick smoke enveloped us like an embrace. All around us, fires were raging; white columns of smoke plunged up into the grey clouds above. These pyres were messengers from this world to the next; their fumes bore the offerings earthly relatives burnt for the deceased.

The smoke mingled with the dust kicked up from the cars, creating a persistent grey-brown smog that settled over the whole scene. The cityscape in the distance was hazy, as if by entering the graveyard, we had already passed from one world to another. The smell of it was choking, yet somehow familiar: warm, earthy and acrid. All around us, ash fluttered from the sky like dry snow, though it was already 30℃ and climbing.

At the grave, we were united with more of my maternal relatives. In all, there were 18 of us, including in-laws, cousins and my cousins’ children. It wasn’t even the whole clan—some had work or other obligations, so weren’t there that year. As we arrived, the usual hellos ensued: wow you’re all grown up, nice to see you, you’re looking well. Once those were through, all 18 of us set onto my grandparents’ grave at once, cleaning the headstone. As my aunt had arrived earlier, she had already done most of the work, so a cursory rub was all that was required.

Here, a note on Chinese tombs is necessary. In Chinese tradition, instead of placing the tombstone behind the coffin, at the back of the burial plot, the tombstone is placed at the front. Husband and wife (sometimes wives, plural) are usually buried on the same site. To the right of the deceased's names is an inscription of their birth and death dates. To the left is a list of descendants. For my maternal grandparents, this list almost trailed off the tombstone itself. As my grandparents died ten years apart, some of the descendants were engraved, but others were simply written on in gold paint; these were the descendants born between my grandfather’s death, and my grandmother’s.

Behind the tombstone is a large, circular burial mound. Tradition dictates that the higher the dirt pile, the more prosperous your descendants. In front of the tombstone is an altar, which lies on a raised platform, where we kneel to pray to the deceased. This section is generally considered the “house” of the grave. In front of the “house”, there’s another large platform, usually tiled or made of stone. This is the “front-yard” of the grave. To the side lies a smaller altar to the God of the Earth, considered to be the site’s “landlord”.

After the tombstone was cleaned and the offerings placed, we decorated the burial mound with hundreds of colourful crepe papers. All 18 of my maternal relatives picked their way gingerly over the dirt, leaving trails of fuschia, teal, canary yellow and white in their wake. “It’s their new year,” my third 阿妗 | Ah Kim explained. The papers that festooned their graves were decorations for their other-worldly home, like stringing up Christmas lights in December.

Then, in order of seniority, my maternal relatives lined up in front of the grave to offer incense. First you prayed to the dirt god. Then, you prayed to the deceased themselves. Commonly, you’d introduce yourself and then ask for the deceased’s blessings and protection. Superstition specified this introduction couldn’t be by name, but by signifier: daughter, son, grandchild, in-law and so on.

When we were done, a big pile of offerings was made on my grandparents’ “front-yard”. Joss paper, folded into little ingots, were strewn over other paper offerings. These were cardboard replicas of anything and everything someone might want in the real-world. Offerings ranged from houses, luxury cars and luggage to clothes, air-conditioning units, iPhones, and even little butler and maid figurines: all rendered in cardboard miniature. Our offerings were relatively simple: piles of money and a few cases of luggage. As the fire blazed, our relatives stood well back—the heat from the flames was blistering in the already muggy heat.

When the pyre was spent, my Aunts knelt down to toss coins on my grandparents’ altar. If the coins showed the same face, then we knew our grandparents hadn’t finished eating the offerings we laid out. When they showed opposite faces, we began to distribute the food to the living: barbeque pork buns, 发糕 | fa gao or prosperity cake, and roast pork belly.

Before we left, we let out a great big string of red firecrackers. No one warned me before they were set, so when the explosion went off I almost choked on a pork bun. CRACK BANG PAP PAP BANG CRACK they went, letting off blinding white sparks.

Finally, each descendant was handed a stack of pale yellow “dollars” made of crepe paper. These were to be thrown high in the air, creating a flurry of fluttering cream notes which rained down upon ourselves and the grave. At least, that was the idea—being unpractised, my stack of notes simply fell in a big clump to the earth. Around me, however, my relatives threw the notes one-, two-, even three-metres into the air, all the while screaming auspicious phrases: HUAT AH!

Despite my vague notion at a grave-visit being a solemn, mournful occasion, I found myself giggling as we left. I couldn’t help it—how could anyone keep a straight face at the sight of ten or so usually sober, middle-aged adults dancing around a grave, screaming and throwing notes into the air? But perhaps that was the point. Cheng Beng was the ghostly new year, and the new year is a joyful occasion. Contrary to the image I had held of Cheng Beng as an event of quiet remembrance, it was a loud, cheerful affair. My Mum, on addressing her parents for the first time in years, cheerfully yelled: “Mum, Dad, I’m home to see you!” Far from being a mournful occasion, Cheng Beng was a chance for loved ones to reunite, clothe their departed in jolly colours, eat a meal, and make it rain ghost dollars.

The next day, we woke up early to do the whole thing over again, but for my paternal grandparents. They were buried in a different graveyard—one for Teochew people, an ethnic subgrouping of Chinese. Although the rites were largely similar, there were a few Teochew-specific rituals that other ethnic groups didn’t have. On one grave, we saw remnants of bleached clam shells scattered over the burial-mound. My Dad explained that some Teochew would eat clams during Cheng Beng and fling the shells over the earth—the more shells, the more descendants.

This time, we were the first to arrive at the grave—my Dad made sure of it. He was the oldest, which meant he had to pay his respects first. In contrast to my maternal grandparents’ well swept grave, my paternal grandparents’ smaller plot was overgrown with long grass and littered with dead leaves. The vegetation had begun creeping over not only the “front-yard” and “house”, but along the tombstone and altar.

Although I had been somewhat disconnected from my maternal grandparents—both had died long before I was born—I felt closer ties to my paternal side. My grandpa, or 公公 | gung-gung, lived to spend part of my childhood with me. I had hazy memories of lying on his belly watching Teletubbies, and holding his hand at the zoo. He passed away when I was eight.

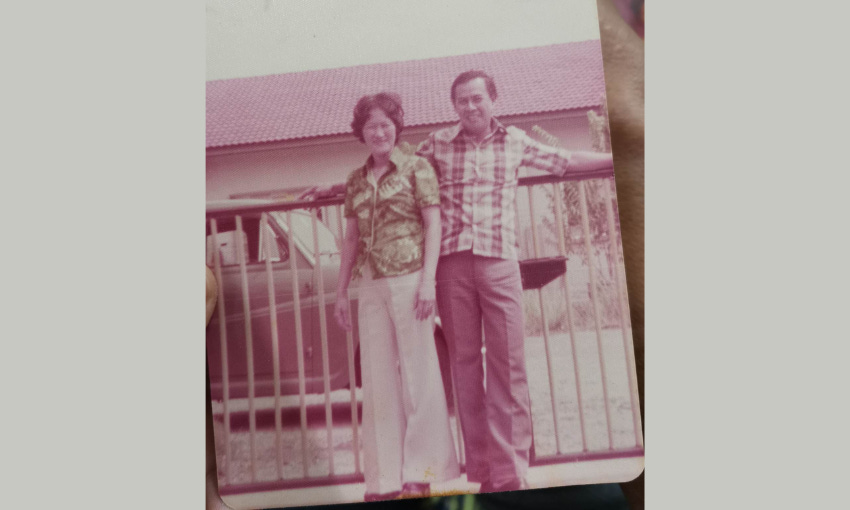

I had never met my grandma, or 阿嬤 | ah-ma. But my Mum and Dad often told me stories about her: an outgoing, well-liked person. From the faded film photos of the 70s, I saw a smiling, stylish woman with curly bobbed hair. Mum tells me that 阿嬤 | ah-ma was so excited to meet me. She even gave me my Chinese name: 佘诗晴 | shé shī qíng. Incidentally, the middle character—诗 | shī—also means “poetry”, or “poem”. Perhaps it’s a coincidence that I grew up to become a writer. But I choose to believe that 阿嬤 | ah-ma bestowed upon me more than just a name.

By the time I was conceived, 阿嬤 | ah-ma was already doing poorly. She had suffered a stroke too young, and wasn’t recovering well. In less than a year, 阿嬤 | ah-ma would have another stroke, which would prove fatal. If she had held on for one more month, 阿嬤 | ah-ma would’ve been able to hold me, her first grandchild.

I thought about this story as my Dad and I swept the grass from my grandparents’ grave. First, we tore at the growth with our hands and feet, kicking the dirt and leaves from my grandparents’ altar and front porch. Then, we borrowed a simple broom made of tied twigs from our neighbours, dusting around the curves of the decorative stone edging. When my paternal aunt and uncle arrived, they brought large jugs of water and rags to finish the job.

As I used the soaked cloth to rub at the grime on my grandparents’ headstone, I suddenly began to feel emotional. There was something intimate about cleaning their headstone—their final resting place. Although it was only cold granite, I had a feeling I was sponging flesh and bone, wiping dirt off weary limbs. Maybe I was being sentimental, but I wondered if 阿嬤 | ah-ma might be happy that I was washing her like she might have washed me, had she lived to see my birth.

After the prayers, we began to build a mound of offerings. This time, in addition to cardboard luggage emblazoned with the Louis Vuitton and Ralph Lauren logos, there was also an air-conditioning unit and a Bentley, complete with a little driver in the window. In life, 公公 | gung-gung had been a car mechanic. I wondered if he was enjoying his car collection in heaven. I imagined him tinkering around in a full garage of vehicles: Rolls-Royces, Bentleys, BMWs. As we stacked the offerings, my Dad joked that they would need a butler to carry all of it—perhaps the driver of the Bentley would do the honours. Finally, as the fire blazed, we threw our paper money over the flames. The heat of the pyre carried the buttercream notes up, up, and up, eventually fluttering down over the colourfully festooned mound and over to neighbouring plots.

“You know, I’m worried that when I die, no one will do this for me,” my Dad said quietly, looking not at me but somewhere over my head. Although I didn’t say it out loud, I decided then and there as I watched the notes fluttering from the sky.

There are many traditions I place no stock in. Some of them are frankly sexist. Others are obscured by time, and yet others are impractical in the modern age. But I would observe Cheng Beng. Now that I was here, I understood the force of tradition. Being the children of migrants, I often felt untethered, adrift in the wide world. But Cheng Beng tied me to my ancestry. It reminded me who I was, where I came from and those I owed it all to—like my 阿嬤 | ah-ma. Come next year, or even the next, or the next, I would also make the long journey to Melaka in April.

And one day—hopefully in the long distant future—maybe I would bring my own children to scatter clams over the earth.

This is so interesting and I love the idea of having a really tangible, symbolic way to remember that you exist in relationship to your ancestors (and maybe descendants too)