i. On filial duty, femininity & armpit hair.

The first in a series of essays examining heritage, identity, tradition, culture and duty on my family trip to Malaysia.

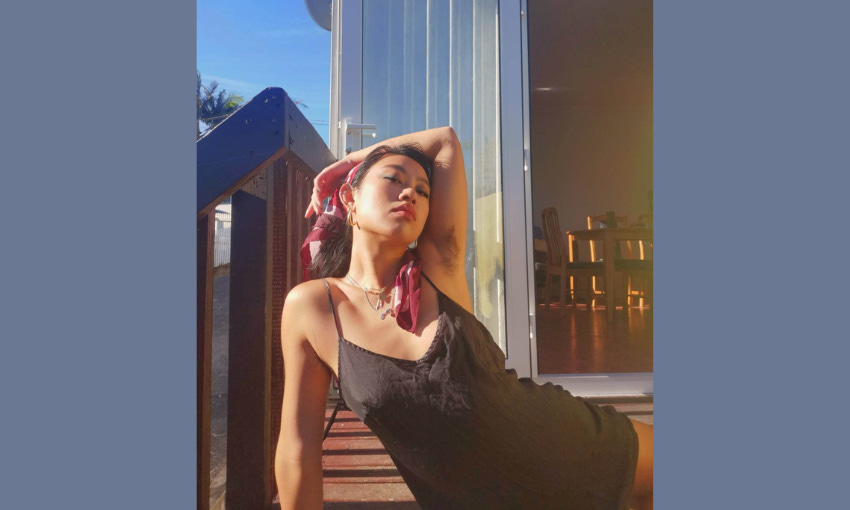

It was during my last visit to Malaysia that I decided to stop shaving my armpits.

I had been an ardent remover of my body hair since it first appeared at the too-young age of nine. I had hit puberty early, and I was disgustingly self-conscious about my oily, pockmarked face; my budding, painful chest lumps; and—worst of all—the thick, black hair that appeared seemingly everywhere. By eleven, I was shaving my body everyday with the shittiest disposable razors five dollars could buy.

I continued shaving my body for almost a decade. Although I didn’t maintain my daily schedule, I was committed to a model of femininity that included being completely hairless from the neck down. That meant shaving every few days, and—somewhat ironically—growing the hair on my head to my waist. In my teen years, I remembered being morbidly envious of my East Asian friends who seemed to be naturally hairless in all the right places and grew the thick, glossy, straight sort of hair on their head. In contrast, the hair on my head was stubbornly wavy, frizzy and sparse, and the hair on my body thick and prickly.

But as I grew older and out of my self-conscious teen years, I also grew away from that rigid ideal of femininity. In my last few years of high school, I had cut my hair short, then shaved it completely during the annual shave-for-a-cure event. It was being bald that radicalised my view of femininity. Without my hair, which I had worn like a safety blanket for years, I felt naked—and free. When I looked in the mirror, I saw a version of myself that existed outside of my fears. I was bald, but I was still beautiful, still feminine, still me. In fact, I felt more like myself than I had before. It took shaving my head to realise that for years, I had been trying to fit square pegs into round holes. So I wasn’t this perfect, feminine ideal—it didn’t make me any less than.

In the wake of this Earth-shattering realisation, I flew to Malaysia with my Mum back before the pandemic. In the humid climate, the constant irritation and profuse sweating caused me to grow a big, tenderly painful red cyst under my right armpit. To help it heal, I stopped shaving under my arms—and I never did again.

As my pit hair grew out, I simply fell in love with it. No more uncomfortable, prickly growing-out stage. No more ingrown hairs. No more discoloured skin. No more cysts. And I learned things about my body that I hadn’t known before. It was an intimate experience. I learned that it tickled when I lifted my arms to a summer breeze; that my B.O was sour and funky after a long day; that armpit hair sheds and grows again like the hair on your head. After a while, I got used to it, and I even liked the way it looked. It was an accessory: a visible fuck-you to gender norms.

Not everyone understood my decision. For the most part, my friends simply shrugged. But reactions ranged from enthusiastic support to quiet confusion to outright disgust. One man, who I slept with on and off for months once told me—post-nut—that I’d be much more attractive without my pit hair. I stared at him from across the pillow; it would’ve been hurtful if it hadn’t been so laughable.

My parents especially hated it. My Dad tried to tease me into submission. “Jungle Jane,” he called me. My Mum took a harder-line. “No man will want you if you don’t shave,” she said. It always made me grimace. Besides being factually untrue, I didn’t want to base my worth on whether men found me attractive. But that was easier said than done. I’d fallen into that trap more than once, and once you fall down that hole, it’s terribly hard to escape.

So I suppose I couldn’t blame my Mum for nagging me. She was simply passing her hang-ups about femininity onto me. My Dad wasn’t immune to misogyny either. Sometimes, he would make little jibes about my Mum’s appearance. And he would police mine too. Sometimes our arguments over my appearance would dissolve into screaming matches. When these happened I’d always be disowned. “I didn’t raise a whore,” my Dad spit.

We’d had these arguments periodically ever since I was a teenager. Although I’m sure my parents would tell it differently, to me, their criticisms were unpredictable. Some days, my Mum would nod approvingly. Other days, a similar outfit would cause an argument. It felt as if I was chasing an invisible, ever-moving goal-post marked ‘The Perfect Woman’. The Perfect Woman would be sexy, but not too sexy. She would be smart, but quiet. She would be beautiful, but modest. Most of all, she would be inoffensive.

During these arguments, I tried my hardest to make my parents understand what they were really saying.

I wanted them to know that women’s bodies weren’t inherently sexual, and they were perpetuating the same patriarchal ideologies that led to victim blaming, to slut-shaming, to sexual violence and gender inequality. But they didn’t understand.

So I tried to understand them.

Besides the stock-standard sexism that comes from being raised in 1980s Malaysia, my parents were also strongly influenced by Confucianism, and a collectivist culture. (Side-note: Confucius himself was a famously sexist asshole—but I digress). In Confucianism, your body is a gift from your parents. That means it’s a sin to harm it in any way—so no haircuts, no tattoos and no piercings. As for collectivism, well, that means that any non-conformity can be heavily punished and stigmatised, either through vicious gossip or public shaming.

My parents grew up in tight-knit family units. The concept of individuality was foreign. Choices were made in a group, for the benefit of the whole. There was no such thing as personal choice—what you did affected the standing of your family. Although it meant that support networks were tight knit, it could also be a mechanism to reinforce certain values—like rigid gender norms. But growing up in New Zealand, individuality was encouraged and celebrated. I took it as a given that I was my own person, and should be allowed my own decisions. I didn't understand why my choices would hurt my parents so much. Choices like choosing not to shave my armpits.

This story doesn't have a neat ending. The line between asserting my autonomy, and pleasing my family is a thin one to walk.

I still believe people should have personal choice—as long as they're not harming others—and I've never been one for rules. I’ve always thought that if I'm not hurting anyone, what does it matter?

Mid-last year, I moved home after five years of flatting. It was partly because of the cost of living, but mostly because I wanted to be closer to my parents. I’m an only child, and I figured it was about time I got to know them as an adult. Although the move was greeted joyously by both my Mum and Dad, I knew it would bring up old issues. And I was right. By September, we had a huge fight. For months, my Dad and I didn't speak. It sounds like a lot of drama over not much: some hair under my arms. Eventually, we reached a compromise that neither myself nor my family was happy with—which I suppose is a sign of a good compromise. Around the house, I would wear sleeves.

As time went by, and with the help of a counsellor, my Dad and I gradually patched things up. I continued to wear sleeves around the house, swallowing my growing resentment. Finally, as the date of our trip to Malaysia neared, I made a decision. I Googled the nearest waxing place, and I booked an appointment.

Nervously, I told my lovely aesthetician that I hadn't shaved since 2019. She assured me the waxing would be painless. And it was—at least, physically painless. In 15 minutes, four years of hair was ripped out at once.

I'm not usually sentimental about hair. I shaved my head once, after all. And the thing about hair is that it grows back. So when I booked the wax, I imagined I might feel indifferent afterward, though maybe a bit sore. But when we were done, as I looked in the mirror at my smooth pits, I felt sad. Despite the fact that I still shaved other parts of my body, I had grown attached to my pit hair.

I couldn’t quite pinpoint what it was that made me sad. Perhaps it was the significance of altering myself to feel accepted by my family. Perhaps it was a type of regret—I had given into pressures that went against my own values, my own sense of self. But as I looked in the reflection, I thought about the gossip that would spread between my aunts if I showed up in Malaysia after four years with hairy pits. I was already too dark, and covered in tattoos. I thought of all the sacrifices my parents had made for me along the way: moving away from their family and working overtime for my tuition. And I thought of all the happy memories we had made since I’d come home: playing mahjong in the sunshine on a Sunday afternoon; eating hotpot and steamed mussels; digging in the sand at Whangaparāoa for pipi.

Surely I could sacrifice my pit hair for a month—right?

Perfect writing, even the old White beat (up?) guys would work with this (Ginsberg, Bukowski, Kerouac etc...) Niice 💇🏽♀️👹🙈🙏🎆👏💎😉